Trumpeter Swan

General Description

The largest of the North American native waterfowl and one of our heaviest flying birds, the Trumpeter Swan is large and white. It holds its long neck straight up, often with a kink at the base. The bill is black, and there is no coloration in front of the eyes. The juvenile is dusky-gray, with a mottled dark-and-light bill that is black at the base. The juvenile plumage persists until at least spring migration, which helps distinguish the Trumpeter Swan from the Tundra Swan.

Habitat

Trumpeter Swans inhabit lakes, ponds, large rivers, and coastal bays. They were historically more common in fresh water than salt water, but this is no longer the case. Their most important habitat requirements are open water, access to food, and protection from disturbance.

Behavior

Trumpeter Swans forage on water and, especially in winter, on land. Their long necks allow them to forage for submergent vegetation without diving. They are a long-lived, social species.

Diet

Plant material makes up most of their diet. Adults eat stems, leaves, and roots of aquatic plants, switching to upland grasses and waste grain in the winter. Washington birds eat cultivated tubers such as sweet potatoes. Young birds feed primarily on insects and other invertebrates, especially in the first weeks after hatching.

Nesting

Trumpeter Swans don't usually nest until they are 4 to 7 years old, but they begin forming their long-term pair bonds at 2 to 4 years of age. Nests are surrounded by water, on islands, beaver or muskrat lodges, or on floating vegetation. Both male and female help build the nest (although the female does most of the work). The nest is a low mound of plant matter several feet across, with a depression in the middle. The nest may be reused from year to year. The females lays 4 to 5 eggs and does most of the incubation herself, although the male may help. The male guards the female and the nest while she is incubating. Incubation lasts for 32 to 37 days. The young are able to swim and feed themselves almost immediately after hatching. The parents tend them and lead them to feeding sites, where the young feed themselves. The young fly at about 3-4 months.

Migration Status

Most southern populations are non-migratory, while northern populations move south in late fall as water begins to freeze. Most migration takes place during the day, and flocks fly low overhead in a V-formation. Migration starts early in spring, and birds often return to the breeding grounds before the water is free of ice.

Conservation Status

Trumpeter Swans once nested over most of North America but disappeared rapidly due to human development and hunting practices. By the 1930s, fewer than 100 Trumpeter Swans remained south of Canada. With habitat preservation, protection from hunting, and reintroduction efforts, Trumpeter Swans have experienced a comeback, especially in the Northwest. They are now found in greater numbers in Washington than anywhere else in the contiguous United States. Of the over 15,000 individuals estimated in North America, more than 2,000 were counted in Skagit County during the 1999-2000 hunting season. Populations are still increasing and expanding their range to other counties in Washington, but they are not without threat. Habitat loss is still an issue, as is lead poisoning. Trumpeter Swans ingest lead shot as grit to help digest hard grains, and as few as three pellets can kill a Trumpeter Swan. Although lead shot is banned for hunting waterfowl in both the US and Canada, it can still be used for hunting upland birds and for trap shooting, which occurs in some of the areas where Trumpeter Swans winter. Swan die-offs from lead poisoning occur periodically. In 1992 a number of poisoned Trumpeter Swans were found, and in 1999-2000, at least 87 died. Since 2000, hundreds of Trumpeter Swans have died of lead poisoning in Whatcom County. The source of the lead shot is not known, but wildlife officials are trying to identify the source, so that they can remove it and prevent this from occurring in the future. Ailing Trumpeter Swans must be removed, as scavengers can also get lead poisoning from preying on poisoned swans.

When and Where to Find in Washington

Trumpeter Swans spend the winter from November to April in the open fields and estuaries of Skagit and Whatcom Counties. Padilla Bay, Samish Bay, and Samish Flats are all areas that Trumpeter Swans frequent. Recently, this range has expanded to Grays Harbor and other areas of western Washington. They are uncommon in similar habitats in eastern Washington during winter. There are currently no Trumpeter Swans breeding in Washington, but a pair has been seen during the breeding season at the Turnbull National Wildlife Refuge (Spokane County) since 1994, and they may breed in coming years.

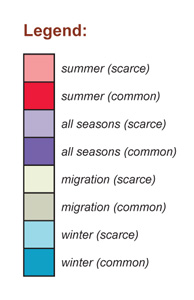

Abundance

Abundance

| Ecoregion | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oceanic | ||||||||||||

| Pacific Northwest Coast | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | |||||

| Puget Trough | C | C | F | U | R | C | C | |||||

| North Cascades | U | U | U | R | R | U | U | |||||

| West Cascades | ||||||||||||

| East Cascades | ||||||||||||

| Okanogan | R | R | R | R | ||||||||

| Canadian Rockies | ||||||||||||

| Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||

| Columbia Plateau | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

Washington Range Map

North American Range Map

Family Members

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor

Fulvous Whistling-DuckDendrocygna bicolor Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis

Taiga Bean-GooseAnser fabalis Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons

Greater White-fronted GooseAnser albifrons Emperor GooseChen canagica

Emperor GooseChen canagica Snow GooseChen caerulescens

Snow GooseChen caerulescens Ross's GooseChen rossii

Ross's GooseChen rossii BrantBranta bernicla

BrantBranta bernicla Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii

Cackling GooseBranta hutchinsii Canada GooseBranta canadensis

Canada GooseBranta canadensis Mute SwanCygnus olor

Mute SwanCygnus olor Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator

Trumpeter SwanCygnus buccinator Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus

Tundra SwanCygnus columbianus Wood DuckAix sponsa

Wood DuckAix sponsa GadwallAnas strepera

GadwallAnas strepera Falcated DuckAnas falcata

Falcated DuckAnas falcata Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope

Eurasian WigeonAnas penelope American WigeonAnas americana

American WigeonAnas americana American Black DuckAnas rubripes

American Black DuckAnas rubripes MallardAnas platyrhynchos

MallardAnas platyrhynchos Blue-winged TealAnas discors

Blue-winged TealAnas discors Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera

Cinnamon TealAnas cyanoptera Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata

Northern ShovelerAnas clypeata Northern PintailAnas acuta

Northern PintailAnas acuta GarganeyAnas querquedula

GarganeyAnas querquedula Baikal TealAnas formosa

Baikal TealAnas formosa Green-winged TealAnas crecca

Green-winged TealAnas crecca CanvasbackAythya valisineria

CanvasbackAythya valisineria RedheadAythya americana

RedheadAythya americana Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris

Ring-necked DuckAythya collaris Tufted DuckAythya fuligula

Tufted DuckAythya fuligula Greater ScaupAythya marila

Greater ScaupAythya marila Lesser ScaupAythya affinis

Lesser ScaupAythya affinis Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri

Steller's EiderPolysticta stelleri King EiderSomateria spectabilis

King EiderSomateria spectabilis Common EiderSomateria mollissima

Common EiderSomateria mollissima Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus

Harlequin DuckHistrionicus histrionicus Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata

Surf ScoterMelanitta perspicillata White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca

White-winged ScoterMelanitta fusca Black ScoterMelanitta nigra

Black ScoterMelanitta nigra Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis

Long-tailed DuckClangula hyemalis BuffleheadBucephala albeola

BuffleheadBucephala albeola Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula

Common GoldeneyeBucephala clangula Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica

Barrow's GoldeneyeBucephala islandica SmewMergellus albellus

SmewMergellus albellus Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus

Hooded MerganserLophodytes cucullatus Common MerganserMergus merganser

Common MerganserMergus merganser Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator

Red-breasted MerganserMergus serrator Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis

Ruddy DuckOxyura jamaicensis